Dan Simmons has seen a lot during the 39 years he’s worked at U.S. Steel’s Granite City Works in Illinois, just outside St. Louis.

From starting out as a general laborer, to swinging hammers on the track gang, to “feeling like Mr. Haney from Green Acres” while trucking around the mill, Simmons took it all in. There were days “you were whistling when you came in, and whistling when you left,” he said.

But nothing compares to what he was seeing by the middle of 2016.

“I have grown men coming into my office, crying,” said Simmons. “You see the pain, the ‘what ifs,’ the blank stares…”

Simmons, 57, is president of the United Steelworkers Local 1899, and some of the grown men coming to him were pipefitters just like Simmons had become during his long tenure, which began in 1978.

However, those men and women weren’t coming to him because they’d been hurt on the job. They were coming to plead for help because they had lost their jobs and, in many cases, didn’t know when they’d land their next one.

Cyclicality in steel production is nothing new, but it wasn’t until 2008 — when the global markets began crashing — that USS Granite City Works endured the first indefinite idling in its history.

Source: Taras Berezowsky/MetalMiner

Source: Taras Berezowsky/MetalMiner

The latest idling of the mill has hit residents of Granite City — and the surrounding region — very hard.

“We had the unemployment office cycling 400 people through at a time,” Simmons told MetalMiner. “The biggest fear is not knowing. If I could have given them a definitive timeframe, they would’ve said, ‘OK, I can handle that.’ But after two to three months, people come to me and don’t know what to do with themselves.”

After the mill went idle a second time in December 2015, some of those workers had been without a job for nearly half a year. That December, more than 1,500 people were laid off — 75% of the mill’s total workforce. Across the country, a total of 13,500 steel workers were laid off between September 2015 and September 2016.

Simmons knows what it’s like to feel that fear of job loss firsthand.

“I got a brother that works here, a brother-in-law that works here, so it’s personal. You worry about where your whole family will be.”

Less than three months after MetalMiner interviewed Simmons in 2016, a political earthquake shook the world — voters elected Donald Trump as U.S. president.

Nearly a year after initiating the U.S. Commerce Department’s Section 232 investigation into whether foreign imports of steel and aluminum posed a danger to the country’s national security, and finally making good on campaign promises to resurrect U.S. manufacturing, Trump ordered 25% tariffs on steel imports and 10% tariffs on aluminum imports to go into effect in March 2018.

Between the election and the Section 232 investigation results, Simmons and his members endured more waiting and more economic hardship.

But after the tariff announcement, their fortunes had changed again.

U.S. Steel announced that one of Granite City’s two blast furnaces would be restarted, and 500 employees would get back to work.

“I’ve been telling these guys for a long time, ‘Fire up,’” Simmons told St. Louis Public Radio shortly after the announcement, “and we’re happy to [see] the smiles of the guys coming up and down my union hall.”

With 500 workers coming back, and the potential to add another 300-400 more if the second blast furnace were to be restarted in the future, according to the Alliance for American Manufacturing, Trump’s tariffs have been welcomed in Granite City. However, it is expected to take up to four months to get all of those initial workers back on the job, according toaccording to U.S. Steel.

No matter how long the good news will last as the next phase of this tariff drama plays out, for Simmons and scores of others in the country’s steel sector and other manufacturing industries, much of the past pain — and future uncertainty — can be traced back to one main source: China.

A History of Unfair Trade?

In its quest to grow its economy over the past two decades, China has become the leading producer — by far — of steel, aluminum, cement and other industrial materials.

According to the World Steel Association, China produced 831.7 million tons of steel in 2017, by far the most of any country. In fact, China’s percentage of global steel output actually increased slightly, up from 49.0% in 2016 to 49.2% in 2017.

Because of this, global steel overcapacity has reached upwards of 700 million metric tons. China's aluminum production has increased from 11% of global output in 2000 to more than 50% today. And imports of paper from China nearly tripled from 2012 to 2014, from 23,600 metric tons to 62,400 metric tons, with eight uncoated paper mills having closed or idled, said Scott Paul, president of the Alliance for American Manufacturing (AAM), in Congressional testimony.

However, China’s economy — and the role of its government within it — operates differently than much of the rest of the world, in that the country is effectively able to export and offer its products much more cheaply to many of its trading partners. Depending on the circumstances, this has tended to spur allegations of “dumping” over the past several decades, and has now come to a head.

Currently, China is considered a “non-market economy” under World Trade Organization (WTO) rules. Achieving market-economy status would ultimately put China on the same level as the U.S. and E.U. in the eyes of the WTO, taking what some already consider a global trade war to new heights.

That last point is what has stirred up controversy.

A change in status would impact Western manufacturers as well as importers, distributors and several other parties on many levels. It could put the final nail in the coffin of entire industries, such as U.S. furniture-making.

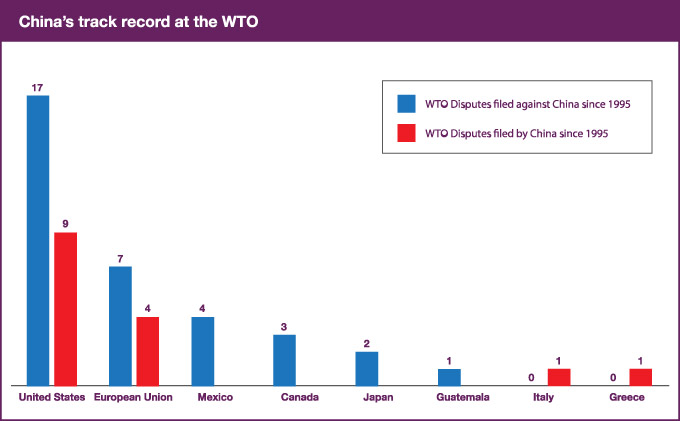

In part, the controversy has become all the more heated due to countless allegations — in the form of trade cases and other trade complaints and disputes — levied by the U.S. and E.U. against China since its accession to the WTO in 2001, essentially maintaining that China does not yet operate as a market economy.

At the end of 2016, China was hoping to receive market-economy status (MES). Unfortunately for China, however, it is still waiting on that status, now just over 16 years since joining the WTO in late 2001 — although the country continues to lobby for it globally.

In China’s defense, after being battered by falling demand and corresponding growth levels the past few years, the country is struggling to deal with supporting its developing economy — and its citizens.

According to the Wall Street Journal, job protection is the government’s key concern, with the primary aim of “maintaining social stability,” according to a provincial Department of Finance official who spoke to the WSJ.

The country’s key tool for that has been to over-produce products such as steel and aluminum, and since Beijing’s plan to shift to a consumption-led domestic economy has cooled lately, those products make their way into China’s export market.

That’s why in 2014 alone, China was the subject of 55% of all global anti-dumping investigations. According to a November 2016 report from the WTO’s Committee on Anti-Dumping Practices, 276 new anti-dumping investigations were launched by 45 WTO members between mid-2015 and mid-2016. Of those, the U.S. initiated 51, trailing only India (66).

As of April 30, 2018, China is listed as a respondent in 40 WTO disputes, trailing only the E.U. (84) and the U.S. (138). Of China’s 40 pending disputes, the U.S. is a complainant in 22 of them, or 55%.

There’s also Section 232 of the — somewhat ironically named, in this case — Trade Expansion Act of 1962.

The Trump administration unearthed the rarely used law to investigate imports of steel and aluminum. The law gives the president the ability to restrict imports of products if it is determined they have a harmful impact on national security. The investigations were launched in April 2017, kicking off a 270-day statutory deadline by which Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross was required to present Trump with a report and recommendations vis-a-vis the two probes. Ross sent the steel report to Trump Jan. 11, 2018, and the aluminum report a week later.

The last time Section 232 was invoked came in 2001, when the administration of George W. Bush looked into imports of iron ore and semi-finished steel. The Department of Commerce ultimately ruled those imports were not a national security threat. (Let’s put a bookmark here — more on Section 232 later.)

In addition, just this past November the U.S. Department of Commerce self-initiated anti-dumping and countervailing duty investigations for the first time in a quarter of a century (in this case, of common alloy aluminum sheet from China). Typically, anti-dumping or countervailing duty probes in the U.S. are spurred by petitions from domestic industry. In this case, the department self-initiated the investigations — a move indicative of an active department under the Trump administration, which has overseen a notable rise in anti-dumping and countervailing duty cases.

The main driver behind the dumping claims is essentially the role China’s government plays in influencing the country’s economy, and — many say, unfairly — subsidizing industries to be more competitive with those of its trading partners. China also stands accused of outright theft of intellectual property from some U.S. companies.

Many parties are concerned China’s foreign trade actions continue to reflect the interplay between its government and its domestic economy, accusations which run contrary to Beijing’s insistence the country has outgrown its non-market-economy status.

Let’s Define a ‘Market’ vs. ‘Non-Market’ Economy

Broadly speaking, the definition of a market economy implies that:

- Prices are determined by supply and demand through free competition

- Investment decisions, production and distribution are also determined by supply and demand

- Economic decisions and price decisions involving goods and services are conducted by a country’s citizens — not the government

For example, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) countries — Canada, Mexico and the U.S. — are classified as market economies.

This contrasts starkly with a centrally planned economy, in which the government shapes and controls everything from costs, prices, wages, output quotas, the value of its currency and more. The former Soviet Union and China are both prime examples; these are considered “non-market” economies (NME).

After the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, former satellites moved from centrally planned to market economies, formally becoming transition economies.

In the immediate years after the WTO came into being in 1995, 10 more transition economies became members, recognizing special treatment in their protocols of accession.

Since China’s accession to the WTO on Dec. 11, 2001, countries such as those in NAFTA — the trilateral trade deal which itself has been the subject of months of negotiations, with a seventh round of talks wrapping up in early March in Mexico City — have treated China as a non-market economy in anti-dumping cases due to the Chinese government’s influence in economic enterprise.

However, based on the Accession Protocol’s language, China believed that after Dec. 11, 2016, it would automatically achieve MES due to the expiration of one particular clause within the protocol.

The interpretation of the language within that specific section is at the heart of the dispute.

Here's The Meat of the Debate

How the Non-Market Economy (NME) Methodology Works

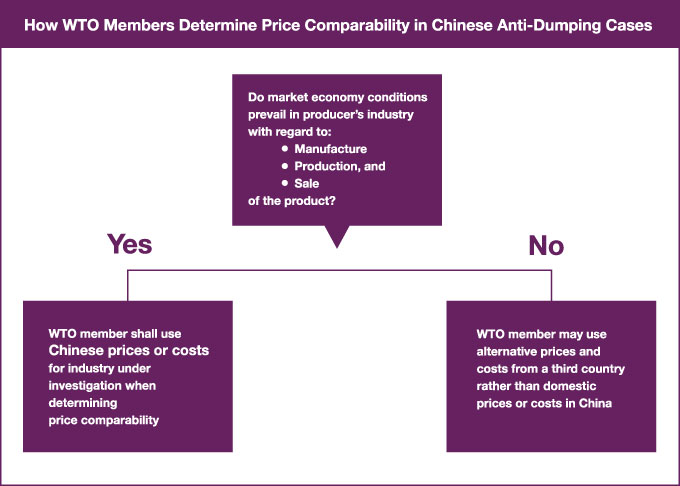

Basically, non-market economies pose a problem when it comes to appropriately determining the margins used to compensate for products unfairly dumped into another market. This is mainly because the two factors used for purposes of comparison — the exporting country’s “home” prices, and its costs of production — are both too skewed in a non-market economy due to heavy governmental involvement. Using either would lead to inaccurately calculated margins.

Therefore, under the General Agreement for Tariffs and Trade (GATT), it was agreed to construct the home market price on the basis of prices from a “third country” — in essence, a similar country with a market economy. The Tokyo Round of 1979 incorporated this component into the GATT, after which it got wrapped into U.S. law, according to this study commissioned by a number of North American steel organizations.

Since the early 1980s, the U.S. Department of Commerce has applied this NME methodology for purposes of calculating anti-dumping margins in cases involving China.

The Legalese at Play: It All Hinges on ‘Price Comparability'

In order for China to join the WTO as a member in 2001, all negotiating parties (including China) agreed to a different standard in that country’s Protocol of Accession regarding anti-dumping investigations.

As part of China’s promise to move toward fully becoming a market economy, that standard required China to demonstrate “that market economy conditions prevailed in the industry producing the product under investigation,” and, if it couldn’t, the importing country could compare prices or costs based on an economy of similar economic development to China — rather than Chinese prices and costs.

The exact language resides in Section 15 of the Accession Protocol:

"In determining price comparability under Article VI of the GATT 1994 and the Anti-Dumping Agreement, the importing WTO Member shall use either Chinese prices or costs for the industry under investigation or a methodology that is not based on a strict comparison with domestic prices or costs in China based on the following rules:

- If the producers under investigation can clearly show that market economy conditions prevail in the industry producing the like product with regard to the manufacture, production and sale of that product, the importing WTO Member shall use Chinese prices or costs for the industry under investigation in determining price comparability;

- The importing WTO Member may use a methodology that is not based on a strict comparison with domestic prices or costs in China if the producers under investigation cannot clearly show that market economy conditions prevail in the industry producing the like product with regard to manufacture, production and sale of that product.

Here’s the kicker: China’s argument for achieving automatic market economy status hinges on one specific sentence in Section 15, which states that “in any event,” the second provision above “shall expire 15 years after the date of accession” — that is, on Dec. 11, 2016.

Nonetheless, more than a year after that date, China is still considered a NME by the U.S. In November 2017, the U.S. formally notified the WTO that it opposed granting China MES.

Certain legal experts argued that based on a plain reading of the protocol language, the automatic expiration would not happen. Attorneys at Wiley Rein, a firm based in Washington, D.C., argued on the grounds that if this was to be the actual "intent of the law," then the rest of Section 15 would be nullified, and based on the length of these types of WTO negotiations and the ways in which treaties such as this one are meant to be interpreted, the expiration was not likely to be honored.

Others, such as the authors of this study, noted that based on the language, WTO “member countries, including the NAFTA countries, can continue to apply the NME methodology (or similar ones) until China (or Chinese producers) can demonstrate that it operates under market economy conditions,” according to the report.

Therefore, the debate boils down to…

- The interpretation of the WTO Accession Protocol, specifically Section 15

- The ability of Chinese producers (and/or the government for entire industries and the economy as a whole) to prove market economy conditions prevail for a particular producer, industry or economy as a whole, meaning WTO importers must use Chinese costs and prices as a basis of price comparison

- How each individual WTO member’s national law allows for China to become a market economy

So Is China a Market Economy Now?

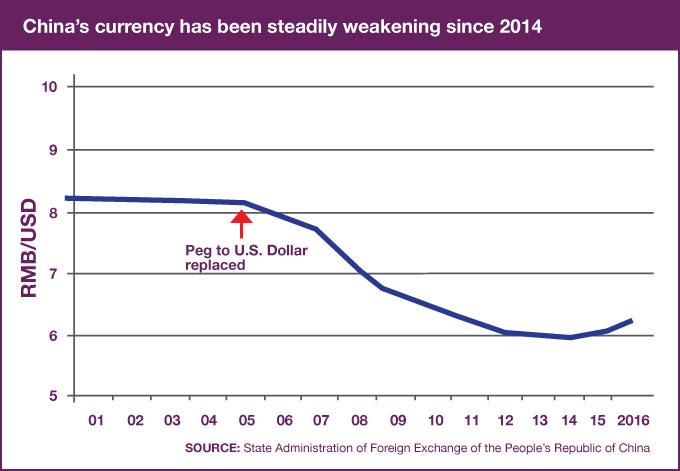

Many indications point to an uphill battle for China in officially proving its market-economy status. Long known as a currency manipulator, China has been accused of purposely devaluing its yuan in the past to gain economic advantage

It should be noted, however, that the Trump administration in April declined to refer to China as a currency manipulator in the U.S. Treasury’s report to Congress titled “Macroeconomic and Foreign Exchange Policies of Major Trading Partners of the United States,” as reported by the New York Times.

“Treasury places significant importance on China adhering to its G-20 commitments to refrain from engaging in competitive devaluation and to not target China’s exchange rate for competitive purposes; and on greater transparency of China’s exchange rate and reserve management operations and goals,” the Treasury report stated. “Over 2017, the Chinese currency generally moved against the dollar in a direction that should, all else equal, help reduce China’s trade surplus with the United States; however, on a broad, tradeweighted basis the RMB was broadly unchanged on net over 2017.”

Government subsidies at local and state levels have also given Chinese companies a leg up on global competition. According to the World Bank and other bodies, China and its government continue to eschew market economy conditions. For example, land prices in particular are subject to comprehensive government control, causing fundamental distortions in land prices in China.

“Because all local governments are the owners of urban land in their jurisdiction, they have strong incentives to supply cheap land for industrial use to generate economic growth,” according to a World Bank report.

The World Bank has also noted that the Chinese government continues to exercise control over prices for transport, energy, utilities and credit, supporting its key manufacturing industries, such as textiles.

Not only that, Chinese state-owned enterprises and how they operate are a cause for concern. According to a Wall Street Journal analysis of nearly 3,000 domestic-listed Chinese companies in 2015, “reported government aid rose to more than 119 billion yuan, or more than $18 billion, last year compared with about 92 billion yuan in 2014.”

China’s Tianjin Pipe Corporation (TPCO), which has an operation outside of Corpus Christi, Texas, is one such example.

According to Tim Brightbill, partner at Wiley Rein, these Chinese companies get preferential capital and other government subsidies to set up steel mills; or, if they don’t get subsidized initially, two years after starting production they begin operating on preferential treatment such as being less subject to regulation, not being traded on stock markets, and enjoying a different ownership structure.

Philip Bell, president of the Steel Manufacturers Association (SMA), noted back in 2015 that when the Texas branch of TPCO applied for membership in that U.S. trade association, it was subsequently informed that SMA only accepted companies whose business was entirely market-based. TPCO responded that the U.S. operation was market-based while “traditionally Chinese.”

SMA did not admit the producer.

China’s official line on market-economy status is evident from China Foreign Ministry Spokesman Hong Lei’s statement in a 2016 press conference: “China has been working faithfully to fulfill its obligations as a WTO member since its accession.”

Although China has made comparatively small strides, such as agreeing to stop steel export subsidies for some of its small companies after receiving pressure from the U.S. Trade Representative’s (USTR) office, the country has a long way to go to prove it operates as a market economy.

Unsurprisingly as these things go, the USTR has stated those strides have not been enough, particularly with respect to WTO rules.

On Jan. 19, 2018, the USTR released its 2017 report to Congress on China’s WTO compliance.

“Today, almost two decades after it pledged to support the multilateral trading system of the WTO, the Chinese government pursues a wide array of continually evolving interventionist policies and practices aimed at limiting market access for imported goods and services and foreign manufacturers and service suppliers,” the report states.

The report is pursuant to the U.S.-China Relations Act of 2000, which requires the USTR to submit an annual report to Congress on China’s efforts toward WTO compliance. This report marks the 16th of its kind delivered to Congress since the act’s passage.

The report is, not surprisingly, decidedly pessimistic vis-a-vis the state of China’s economic operating conditions, and, by extension, is bearish with respect to the feasibility of granting China the market-economy status it wants.

“Many of the policy tools being used by the Chinese government…are largely unprecedented, as other WTO members do not use them, and include a wide array of state intervention and support designed to promote the development of Chinese industry in large part by restricting, taking advantage of, discriminating against or otherwise creating disadvantages for foreign enterprises and their technologies, products and services,” the report continues.

Taking it a step further, the report indicates that the overall structure of WTO rules might not even be sufficient to address the challenges presented by the nature of the Chinese economy.

“While some problematic policies and practices being pursued by the Chinese government have been found by WTO panels or the Appellate Body to run afoul of China’s WTO obligations, many of the most troubling ones are not directly disciplined by WTO rules or the additional commitments that China made in its Protocol of Accession,” the report’s executive summary states.

“The reality is that the WTO rules were not formulated with a state-led economy in mind, and while the extra commitments that China made in its Protocol of Accession disciplined certain state-led policies and practices existing in 2001, the Chinese government has since replaced them with more sophisticated – and still very troubling – policies and practices.”

Who Decides Whether China Gets Market Economy Status?

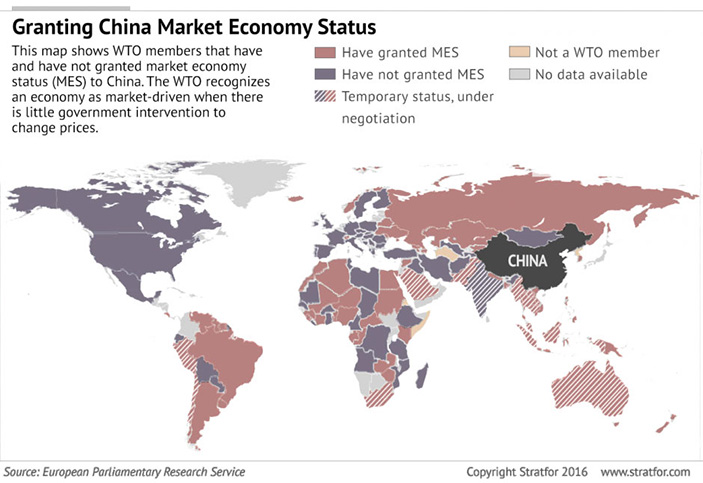

With all the talk surrounding the WTO’s role in determining China’s market-economy status, it is up to individual countries’ governments to make the MES decision.

Certain WTO member countries, such as Australia, have already granted China MES, largely through existing trade agreements.

Politically and economically, the E.U. (China’s largest trading partner) and the U.S. are seen as the most important decision-makers. The E.U. had already made its decision well before the U.S. did in November 2017. On that front, in 2016 the E.U. adopted a new five-year strategy for dealing with China on trade, which aimed to promote “reciprocity, a level playing field and fair competition across all areas of co-operation.”

Although the U.S. decided to continue treating China as a non-market economy country, U.S. law allows an entire country, producer or industry to “graduate” to market-economy status and to show why Chinese prices or costs should be used for dumping comparisons.

The U.S Decision – Six Criteria to Say Yes to MES

U.S. law requires the International Trade Administration, under the U.S. Department of Commerce, to consider six criteria in determining if a country has achieved market economy status:

- The extent to which the currency is convertible into the currency of other countries,

- The extent to which wages in the country are determined by free bargaining between labor and management,

- The extent to which joint ventures or other foreign investments are permitted,

- The extent of government ownership or control of the means of production,

- The extent of government control over the allocation of resources and over the price and output decisions of enterprises,

- Other factors considered appropriate by the administering authority.

The request to consider China a market economy had to formally come up in a new U.S. trade case for Commerce to begin the process, according to Tim Brightbill, partner at Wiley Rein LLP in Washington, D.C. — essentially any anti-dumping case in which China is a respondent.

In its affirmative preliminary ruling on Chinese aluminum foil, the DOC found that “exporters of aluminum foil from the People’s Republic of China (China) sold their product at prices that resulted in preliminary dumping margins of 96.81 percent to 162.24 percent to be applied, based on factual evidence provided by the interested parties using the Department’s standard non-market economy dumping methodology.” In an Oct. 26, 2017 memo, the Department of Commerce concluded that China is not a market economy. According to the memo: “The basis for the Department’s conclusion is that the state’s role in the economy and its relationship with markets and the private sector results in fundamental distortions in China’s economy.”

In late November 2017, the U.S. formally notified the WTO that it opposed granting China market-economy status.

Latest Trade Developments

Many traditional anti-dumping and countervailing duties cases are still in progress, alleging China has subsidized or dumped everything from metals to chemicals. U.S. Commerce recently placed final import duties of 265.79% on all investigated Chinese producers of cold-rolled steel because none of them responded to requests for information during the investigation.

On Jan. 17, 2018, the Department of Commerce issued a preliminary affirmative determination in its countervailing duty investigation of steel flanges from China (and India). In that case, the department calculated countervailable subsidies of 174.73% for China. On April 6, the Department of Commerce issued a final affirmative determination in the steel flanges cases, sending it to the U.S. International Trade Commission for final review (a decision there is expected on or around May 21, 2018). Imports of steel flanges from China in 2016 came in at an estimated value of $16.3 million, according to the DOC.

Just before that, the U.S. International Trade Commission voted to continue the Department of Commerce’s self-initiated anti-dumping and countervailing duty probes of common alloy aluminum sheet from China. In April, the DOC issued a preliminary affirmative determination in the case, calculating subsidy margins of as high as 113.3%.

With respect to Chinese aluminum foil, the U.S. International Trade Commission followed the DOC’s verdict by determining that aluminum foil imports from China have “materially injured” U.S. industry and have benefited from subsidization. The DOC had calculated anti-dumping margins for Chinese respondents as high as 106.09% and countervailing duty margins as high as 80.97%. According to the DOC, Chinese aluminum foil imports in 2016 were valued at $389 million. Imports of aluminum foil from China increased by nearly 40% between 2014 and 2016.

As for the Section 232 aluminum probe, the Department of Commerce announced that Secretary of Commerce Wilbur Ross had submitted his report to President Trump on Jan. 19, 2018. Among other groups, the Aluminum Association has consistently urged the administration to enact 232 action that impacts China but does not negatively impact other important trading partners, like the E.U. and Canada.

“The association supports actions that specifically address Chinese overcapacity, and protect trading relationships between the U.S. and critical partner countries which are crucial to a thriving domestic aluminum industry,” said Heidi Brock, Aluminum Association CEO and president, following the announcement that the 232 aluminum ball had been put in Trump’s court.

On the steel front, the Chinese government in November 2017 began a series of efforts to cut capacity, billed as a large-scale plan to crack down on rampant pollution in the country. Despite those cuts beginning at the outset of the winter season, China closed 2017 having produced 831.7 million tons (MT) of steel, up 5.7% from the 786.9 MT produced in 2016, according to the World Steel Association. China’s share of global steel production even increased slightly in 2017, sitting at 49.2%, up from 49.0% in 2016.

Many have questioned the efficacy of the cuts, as new production has come onstream during that time, in some cases effectively negating the efforts. Even so, the Chinese government in February 2018 announced it planned to meet its goal of cutting capacity by 150 MT — originally targeted for 2020 — by the end of 2018, Reuters reported.

Nonetheless, in March Trump opted to impose tariffs on steel and aluminum imports of 25% and 10%, respectively. Temporary exemptions from the tariffs were initially granted to a select few, those being: Canada, Mexico, Argentina, Australia, Brazil, South Korea and the E.U. In April, the U.S. announced a long-term exemption for South Korea — in tandem with an agreement in principle on a revamped U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement (KORUS) — that included a quota equivalent to 70% of South Korea’s average annual steel exports to the U.S. between 2015-2017. Then, just before the May 1 deadline, the U.S. announced long-term exemptions for Australia, Argentina and Brazil, and a 30-day extension of the temporary exemptions for the E.U., Canada and Mexico.

U.S. steel prices have received a boost from the Section 232 ruling. According to MetalMiner IndX data, from March 1-April 29, the price of cold rolled coil (CRC) has risen 12.6%. Hot dip galvanized (HDG) is up 14.3%. Hot rolled coil (HRC) is up 14.6%. U.S. steel plate is up 16.7%.

Meanwhile, on April 5 China requested consultations with the U.S. over the steel tariff through the WTO’s dispute settlement mechanism.

“The 232 measures of the US was actually trade protectionism in the guise of safeguarding ‘national security,’” China’s Ministry of Commerce said in an official release. “On the one hand, the US excluded some countries and regions selectively, and on the other hand, the US slapped duties on some WTO members including China. The US practice severely violated the non-discrimination principle of the multilateral trading system and its commitments on tariff concession of the WTO and the rules and disciplines of safeguards, and harmed the legitimate interests of China as a WTO member.”

There are also still ongoing intellectual property theft cases being investigated under Section 337 of U.S. trade law involving allegations by U.S. companies such as: U.S. Steel; Allegheny Technologies, Inc.; Alcoa, Inc.; and the U.S. branch of multinational SolarWorld AG.

The 'One-Million-Dollar Question'

Trump met with Chinese President Xi Jinping at Mar-a-Lago in April 2017, the beginning of his administration's attempts at dialogue with China regarding its economic policies.

The dialogue, dubbed the U.S.-China Comprehensive Economic Dialogue (CED), aimed to address “macroeconomic policy, financial stability, currency and energy issues,” according to the aforementioned USTR report to Congress.

In May, a 100-day action plan from China was formed, with both the U.S. and China drafting outcome goals. However, by the first CED meeting in July, “no outcomes were achieved,” according to the USTR.

Trump met with the Chinese president in Beijing in November, at which point the USTR report makes clear that the U.S. team was not looking for talks like those held in the spring, talks that “only achieved isolated, incremental progress on Chinese trade and investment barriers.”

The USTR report runs along these lines for 148 pages, addressing a wide range of topics, ranging from corruption to land and labor laws, among many other things.

In short, the U.S. does not seem inclined to budge on its determination of China’s non-market economy status.

“China largely remains a state-led economy today, and the United States and other trading partners continue to encounter serious problems with China’s trade regime,” the USTR report states. “Meanwhile, China has used the imprimatur of WTO membership to become a dominant player in international trade. Given these facts, it seems clear that the United States erred in supporting China’s entry into the WTO on terms that have proven to be ineffective in securing China’s embrace of an open, market-oriented trade regime.”

Not surprisingly, China pushed back against the USTR report. Gao Feng, a spokesman for China’s Ministry of Commerce, called the report’s claims — that China had not made much progress since its WTO accession in 2001 — false.

“Many arguments in the reports not only ignore but also falsify the facts, and are self-contradictory," Feng said at a news conference in Beijing, according to one report.

In another report, Feng decried what China perceives as a rise in U.S. protectionism.

“We’ve noticed recently that protectionist voices have been rising in the U.S.,” Feng was quoted as saying in one Reuters report.

Trade tension has only continued to rise in recent months.

In August 2017, the USTR launched a Section 301 probe of China, seeking to determine whether “acts, policies, and practices of the Government of China related to technology transfer, intellectual property, and innovation are unreasonable or discriminatory and burden or restrict U.S. commerce.”

Tensions truly ramped up when President Trump announced in March that the U.S. was considering slapping approximately $50 billion in tariffs on Chinese goods. In the announcement March 22, Trump said he had asked Chinese President Xi Jinping to work to reduce the U.S. trade deficit with China by $100 billion. The U.S. ran a trade deficit in goods of over $375 billion in 2017; through the first two months of 2018, that deficit is just over $65 billion, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

In early April, the USTR unveiled a list of 1,300 Chinese products which could be hit with a 25% tariff. The list included motor vehicles, televisions, and industrial equipment, among a wide range of products.

Not long after, China responded with the threat of $50 billion in tariffs on U.S. goods, marking a significant escalation in tensions and sparking fretting about the potential for a trade war between the two countries. Trump’s subsequent announcement of an additional potential $100 billion in tariffs on Chinese goods did not do much to allay those fears.

Speaking of Section 301, the USTR recently released its annual Special Section 301 report, in which it identified a total of 36 countries to be placed on its Priority Watch List or Watch List vis-a-vis intellectual property enforcement.

China was included on the Priority Watch List for the 14th consecutive year. Despite ongoing efforts to overhaul its regulatory framework with respect to IP rights, the USTR report claims those efforts have not been good enough.

“The state of intellectual property (IP) protection and enforcement in China, and market access for U.S. persons that rely on IP protection, reflect the country’s failure to implement promises to strengthen IP protection, open China’s market to foreign investment, allow the market a decisive role in allocating resources, and refrain from government interference in private sector technology transfer decisions,” the Special Section 301 report states. “While some positive developments have emerged in this complex and fast-changing environment, right holders continue to identify the protection and enforcement of IP, and IP-related market access barriers, as leading challenges in what is already a very difficult business environment.”

On the one hand, you have the U.S., with its Section 232 tariffs, accusations of intellectual property theft and its ongoing opposition to market-economy status for China. On the other hand, China sees the Section 232 measures as falling afoul of WTO rules and stretching the definition of what constitutes “national security,” and has expressed the intent to defend itself — and its Made in China 2025 strategic plan — against what it perceives to be undue U.S. protectionism.

Undoubtedly, trade tension between the two countries is only growing. With the Section 232 verdict and a host of other trade case verdicts coming down (or pending), not to mention the ongoing WTO saga, it’s difficult to see that tension slackening in the near future.

So, the million-dollar question is: how can the world bring China and its developing economy into a proper place within the WTO and the global trade ecosystem, while preserving jobs and economic prosperity for Western trading partners?

It’s a complex question that has no easy answer.

“There are lot of factors that go into the mosaic that makes up our economic relationship with China,” conceded Scott Paul, president of the Alliance for American Manufacturing.

Indeed, there is no easy fix. For now, an amicable resolution seems far off — even further off is China’s inclusion among the world’s ranks of market economies, unless a truly comprehensive wave of economic and governmental reforms takes place in the country.

China has grown exponentially in the nearly two decades since its accession to the WTO. Throughout that time, there were expectations in the West that China would embark upon a path toward an economy driven by free-market principles. That has not happened — in some cases, central control of Chinese industry has tightened.

What Comes Next?

So, the international trade community is at an impasse.

The election of Donald Trump has certainly changed the tone of the relationship, to put it lightly. Whether the Trump administration is successful in enacting trade policy vis-a-vis China that benefits American industry remains to be seen. However, at least in word, Trump has embarked upon a more aggressive Chinese trade policy, and underscored the U.S.’s opposition to China receiving market-economy status under current conditions.

As for the WTO, which will serve as a forum for dispute settlement between the U.S. and China, it is an organization that has come in for significant criticism from the U.S., including from the president, who in March said the WTO has been very “unfair” to the U.S.

Trump is not alone in holding a dim view of the WTO.

“The problem that we have is … we are Boy Scouts,” said Barry Zekelman, CEO of Zekelman Industries, during his appearance on The MetalMiner Podcast in late 2017. “We sit there and worry about the WTO. The WTO is a farce. … [The U.S.] is the biggest economic engine on the planet and yet we have one vote at the WTO. It’s ridiculous. The WTO is designed to take advantage of America and its markets.”

For now, the two countries exist in a state of simmering tension. The tariff threats lobbed back and forth in April have yet to go into effect (as of this update), but each verbal jab on that front reverberates like a crack of thunder announcing the imminent arrival of a larger storm.

A team of U.S. trade officials arrived in Beijing on Thursday, May 3, to discuss trade with their Chinese counterparts. Late on May 2, President Trump tweeted: “Our great financial team is in China trying to negotiate a level playing field on trade! I look forward to being with President Xi in the not too distant future. We will always have a good (great) relationship!”

Whatever happens, one thing is clear: the coming months will be crucial for the U.S.-China trade relationship.

Taras Berezowsky, Lisa Reisman, Jeff Yoders, Nick Heinzmann and Fouad Egbaria contributed to this article. Follow them on Twitter @tberezowskyMM, @lreisman, @n_heinzmann and @FEgbariaMM

Updated: May 14, 2018